RIP the great Peter Owen who passed away yesterday aged 89 after a long illness. Owen is one of the unsung heroes of literary culture, an independent who, like John Calder and Marion Boyars, brought into print in the 50’s and 60’s many literary greats who were at that time unknown in Britain or only available in expensive import editions. His roll call of world class authors takes the breath away: Jean Cocteau, Anna Kavan, Herman Hesse, Peter Vansittart, Henry Miller, Joseph Roth, Natsume Soseki, Yukio Mishima, Shusako Endo, Paul Bowles, Andre Gide and Anais Nin.

A working class boy at a run down northern comprehensive school, I relied on libraries and bookshops to track down much prized authors who I had only heard of through literary gossip and the recommendations of fellow enthusiasts. My main source for Owen’s beautifully made little hardbacks was Waterstone’s in Deansgate, Manchester and on special occasions I would nick off school especially to train down to London to go to Foyles in Charing Cross Road where in an inspired move the novels were shelved by publisher rather than author and Foyles featured a whole bay of Peter Owen titles. I still have several of my favourite novels that he published as highly collectable little hardbacks with distinctive dust jackets: The Sheltering Sky; Ice; The Death of Robin Hood; The Confessions of A Mask; and Jeremy Reed’s great book on the Dark Muse—Madness: The Price of Poetry.

Peter Owen was born Peter Offenstadt in 1927 in Nuremberg where his parents owned a leather factory. The city became notorious for holding Nazi rallies starting in 1923 and the Peter’s parents feared for their safety, sending their son away to England at the age of five to stay with his grandparents. The rest of the family sooned joined him and settled in north London, anglicising the family name. Owen recalls a lonely childhood assauged by reading books borrowed from his eccentric Uncle Rudi’s extensive library which included Tolstoy, Dickens, Lawrence, Thackeray and Robert Graves’ Claudius novels. After a short stint in the RAF Owen tried to launch a career as a journalist but found it something of a closed shop so he decided to become a publisher instead.

Aged 21 he went in to business with Neville Armstrong, aided by the paper quota he was allotted due to his time in the air force, working for The Bodley Head’s Stanley Unwin (“a dreadful old shit”), In 1951 Armstrong bought him out of the business for £500 and added to this sum a bank overdraft of £350 (guaranteed by his mother) and armed with one typewriter he started his own publishing company.Owen did much of the packing, sales and distribution himself, recalling, ‘You have to be willing to work like a dog for at least five years to make a go of it as an independent publisher. An amateur must not touch it. Only someone who knows the trade stands a chance.’ His first secretary was Muriel Spark who started work for Owen after completing her first novel, Robinson. She remembers the publisher fondly in her autobiography, Curriculum Vitae:

‘While waiting for my novel to appear, I worked part time at Peter Owen the publisher who was interested in books by Cocteau, Herman Hesse, Cesare Pavese. It was a joy to proof-read the translations of such writers. I was secretary, proof-reader, editor, publicity girl; Mrs Bool was secretary, office manager and filing clerk; and Erna Horne, a rather myopic thick-lensed German refugee, was the book keeper. We were very attached to each other, there in the office at 50 Old Brompton Road, with one light bulb, bare boards on the floor, a long table which was the packing department, and Peter always retreating to his own tiny office to take phone calls from his uncles; one of them worked at Zwemmer the booksellers and gave us intellectual advice, the other was a psychiatrist’.

‘Muriel at that point was a great friend,’ remembered Owen in a recent interview.’She was very helpful to me when I had a breakdown. But then, when she was getting famous, she started moving around with the Queen of Greece.’ Spark later fictionalised her experience as Peter’s secretary in one of her best and funniest novels, A Far Cry From Kensington.

‘He’s the last survivor, still active, of those great immigrant publishers who fled tyranny in Europe and helped the British defend themselves against their own philistinism,’ said Duncan Fallowell at the 60th anniversary of the publishing house.’Publishing is now a rather minor branch of the entertainment industry. But literature is the greatest of the arts. The new generation of publishers is fed on the idea that a book has to be rubbish. Peter is a wonderful example of a person who thinks that books should not be rubbish.’

Owen’s talent was to pick up on distinctive literary authors outside of the mainstream, ‘writing slightly out of the ordinary’, long before they caught on with general readers (many of them actually never caught on at all, but retain cult status); writers such as Anna Kavan, Jeremy Reed, Paul Bowles and Peter Vansittart.His first great success was the publication of Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha: despite having won the Nobel Prize in 1946 Hesse was unknown in Britain, “we were one of the only publishers seeking out such writers. No one had the foresight to get into Hesse, they didn’t even know he existed or know who he was”

Peter Owen became known as the publisher of unusual and avant garde writing and his early lists contained many writers who were obscure at the time but are now an established part of the literary canon: Yukio Mishima, Henry Miller, Anais Nin, Joseph Roth. John Self, writing in The Guardian suggests that Owen’s secret was to have great taste in writing and the confidence to back writing that others found odd and ‘uncommercial.’:

‘when we describe books as “commercial”, all it means is that they reach a wide range of tastes. Uncommercial books are by definition less likely to strike a common chord and, to me at least, are consequently more interesting. Even if a particular book doesn’t tickle me, I’ll be glad I read it because it showed me something different, which much literary fiction from mainstream publishers does not’.

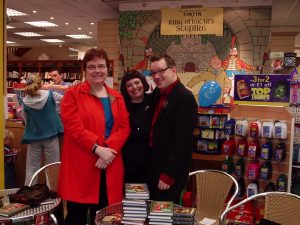

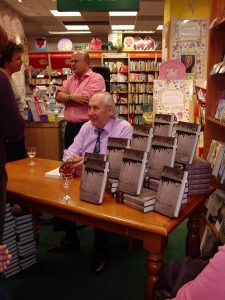

I agree that there is always a market for Owen’s novels, albeit at times a very small one, but booksellers who know their customers can always sell his books. When I was the manager of Ottakar’s bookshop in Putney and hearing through one of the reps that I was a fan of his titles, Peter would often phone me up out of the blue to remind me that he had a new book out, quirky and suprising titles like Arto Paasilluna’s Year of the Hare which his mellow cultured bellow assured me would go down well in literary London.

Certainly today’s literary landscape would be very different without him. D.J. Taylor, author of The Prose Factory: Literary Life in Britain Since 1918 said:’I doff my cap to him. His list is full of the esoteric and the avantgarde. If it hadn’t been for Peter and his one man band doing it all off a kitchen table in SW5 none of it would have happened.’ Peter Owen had that great talent, an unerring eye for good literature and combined with sharp business sense founded a publishing house that remains independent today. There are fewer and fewer of these rare souls still with us: Gary Pulsifer, founder of Arcadia Books, and Peter Owen’s friend and protegee, passed away earlier this year. There are a few who still carry the torch such as Christopher MacLehose, Chis Hamilton-Emery of Salt and Will Shutes of Test Centre who are bold and innovative publishers to whom we readers and booksellers have much to be grateful for. Wherever he is I’m sure Peter Owen would raise a glass to this rare breed.